Judith Fegerl is an Austrian artist working with energy technologies including solar panels. Her projects that engage old solar panels offer a reflection on their origin and place in society, especially as we transition to more sustainable energy systems. The PHOTORAMA team had the opportunity to meet Judith and asked a few questions about her work and the role of artistic approaches in the context of the energy transition.

Interview:

Laure-Anne (PHOTORAMA): Thank you Judith for taking the time to talk to us. In 2023, you exhibited a solar sculpture in Vienna’s MuseumsQuartier, titled “habaï ne sï natena, se paï tanïmena/converter“. What was that sculpture about and what does the name mean?

Judith: the title of the solar sculpture“habaï ne sï natena, se paï tanïmena” is a quote from a science fiction movie by Luc Besson[1] and it means “let us give back to nature that which she gave to us”. In the movie, an extraterrestrial species is able to transform energy from one very condensed state to a usable other state, and by that honouring nature and a harmonic way of life. The sculpture quotes and reenacts this, as it converts solar energy derived from the sun into grow light at night. This technological light shares similarities with natural sunlight in supporting plants to grow.

The form and aesthetics of the sculpture convey the idea of an organic structure with legs and tentacles trying to connect. Another influence was electronic parts like on a circuit board, such as transistors. The sculpture’s legs thrive to penetrate the ground. It is connected to the power grid, and feeds its electricity into it. Often the supporting structures are not visible to us humans, we prefer them underground, somewhere hidden. The solar-sculpture points to the huge networks that we are depending on. Showing aspects of hidden infrastructure and underlying systems is central to my work.

Laure-Anne: As the sculpture is connected to the grid, it means that it is actually producing electricity?

Judith: Yes, it is constantly feeding electricity into the power network. My sculptures are actually doing the stuff, that they seem to be made for. This is very important to me. The solar sculpture contributes far more than it consumes.

Laure-Anne: You often include PV in your artwork. Why this interest in PV?

Judith: I was always interested in electricity, a phenomenon that was more or less ignored in fine arts during the last decades. My interest in PV as a specific technology comes from its ability to harvest, capture and convert energy. In addition to its function, the aesthetics of PV haven’t been documented or discussed. In my research I often encountered loudly expressed opinions about the „ugliness“of PV panels. That aspect was very much stressed in the media and solidified in people’s minds. The aesthetics of photovoltaics was something that kept people from installing PV, and kept whole areas from transitioning to clean energy. I wanted to address that by using art to display PV history.

What is it? How does it look? Where does it come from? How old is it? Who invented it? All these exciting facts were not shared. I also cherish the fact of a more decentralised electricity supply.

Laure-Anne: Your work seems to be a lot about explaining and understanding what we don’t even think about usually. Do you feel that there is also a normative aspect in engaging with PV through your artwork?

Judith: Beyond my own, private fascination for technology, I like to contribute to advancing the climate-friendly technology transition. To raise some awareness, or to reduce prejudice, help educate or just put information, visions, ideas and pictures out there. For another work, I use unregulated PV-generated electricity to create paintings, whose composition shows how solar electricity manifests via an electrochemical process. The pieces are called „full spectrum“ and „solar series of electric shocks“.

Laure-Anne: Where did this interest come from in the first place? Can you explain it? Did you have some exposure to technical studies or topics?

Judith: As a child I was fascinated by the invisible force driving things – very simple things such as a battery driving a motor or a light switch. I was curious about this energy source. You can take it with you as a battery, or you just plug something in, and then, you know, it works. It felt like magic. That wonderful feeling I had as a kid is something, I try to preserve and to evoke with my artwork.

Laure-Anne: As you know PHOTORAMA deals with the ‘downsides’ of photovoltaic uptake, which is the amount of waste and our inability, maybe at some points, to handle this waste. Have you considered recycling processes in your work? Or are you including some circularity element, or maybe the potential downsides of PV uptake?

Judith: The difficulty in PV recycling was one of the starting points for me working with the photovoltaic material, when I developed the sculpture „sunset“ for the Austrian Sculpture Park near Graz. The sculpture park is partly erected on a landfill. So I decided to discuss insufficient procedures in PV recycling, addressing the vast amounts of old panels that are going to be replaced by new ones within the next decade. I wanted to highlight that there are no procedures in place to harvest and recycle valuable minerals and metals like silicon, copper, silver, lead from old panels. There is an ever-increasing demand for those materials, and they are mined under extremely problematic circumstances.

The only positive aspect of low recycling rates of deinstalled PV panels was at the time, that there were still plenty of old ones around. I started gathering and collecting different kinds of panels and cells with striking designs that reflect the state-of-the-art production method of specific periods in history.

I also contacted research groups like OFI (Österreichisches Forschungs- und Prüfinstitut) and the PVRE group at Montan University in Leoben, worked as an artist in residence at the AIT (Austrian Institute of Technology), to find out more about what potential is still inherent to 20- or 30-year-old panels apart from stripping them for their glass and frame. Is it possible to repair joints and soldered parts or replace singular cells, as well as sealing the composite layers once they are worn out?

I wanted to combine all this information including my own fascination for the material and its magical potential to turn sunlight into electricity into something that brings people closer to the subject and the material itself. Usually, PV panels are always far away. They are mounted on roofs, they are behind fences, somewhere distant so that most people never go close enough to have a decent look or even touch.

I wanted to change this, bring the history of photovoltaics close, and provide a possibility to enjoy an emotional moment with the stunning facets of this technology. I changed the surrounding context and transformed old PV panels into artworks.

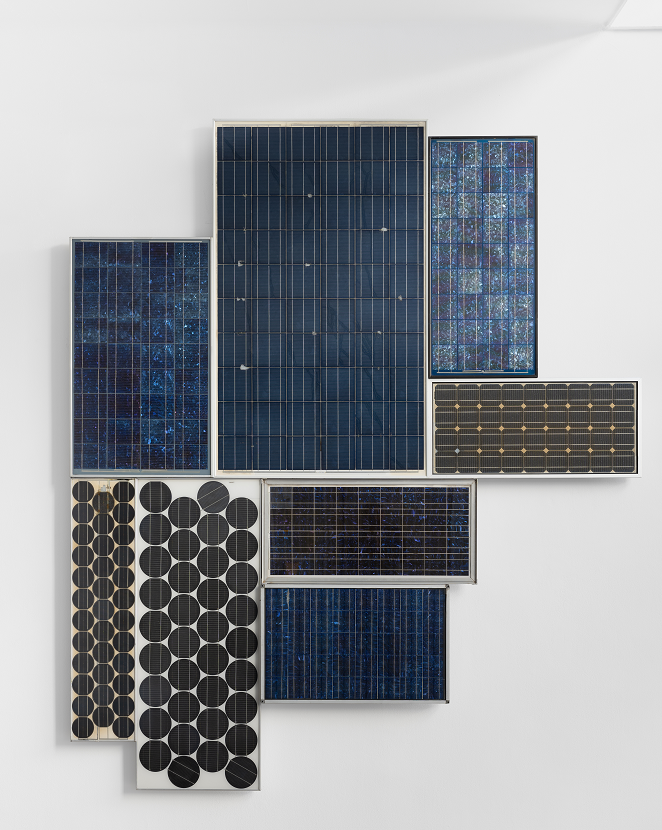

I am fascinated especially by the older PV products that have these polycrystalline structures, all glittery and shiny or different in shapes, colours and structures. Panels display design features of the very time they have been produced in.

To my surprise and exceeding my anticipation a large number of exhibition visitors didn’t even recognise PV panels but were utterly stunned by the beauty and complexity of the material, asking questions and were fascinated by explanations, facts and the history of that technology. Artworks from the series „sunset“ and „last light“ are now represented in major art collections.

Laure-Anne: In terms of material or?

Judith: Just the way they are, cell structures, cell designs, even the wiring. The wiring is comparable to textile patterns or drawings of the time. In order to share these observations, I combined different kinds of solar panels, different shapes and sizes, in a manner you would never ever encounter in a PV-array or PV-plant: to generate the most output, solar panels of the same kind and built need to be connected serially, due to functional reasons, obviously.

The artworks of the series „last light“ represent a diversity of PV texture, a development, and a historic timeline by juxtaposing differing PV elements in a dense patchwork.

Another wonderful thing is, that strictly speaking, the cells still work. Even when not connected they carry an active potential when exposed to light. In some way, this brings up the magic again.

Laure-Anne: When you describe this patchwork of different solar panels, it’s fascinating, and at the same time it creates a lot of problems for the recycling industry, because the fact that throughout the years, they have developed many different types of photovoltaic modules, makes it extremely hard to find processes to recycle photovoltaics.

In the beginning, we talked about the one sculpture that you had at MQ, and how it reflected this purple light, right? Have you found other examples that also do this on the industrial scale? Or would you find it interesting for photovoltaics to use this purple light to grow food?

Judith: I think I read about vertical farming projects in Amsterdam where PV is used to power grow lights inside. I don’t know if they’re purple though.

I think that the more efficient photovoltaic cells become, the more applications will transition. In a laboratory setting, PV is around 40% of efficiency and in commercial use, around 24-25%, or something like that. There is still a long way to go.

Laure-Anne: You mentioned that you worked with old panels. How easy is it for you, or how hard was it for you to get those panels in the first place?

Judith: In the beginning, I went to landfills or sites that collected trash. I also bought quite a lot second-hand. After a while, people started offering certain kinds of panels to me, asking if I could use them for my artwork. I like to think that people cherished the idea that their early solar panels have a second life, other just than being trash.

I support the approach of keeping equipment you already have for as long as possible.

Laure-Anne: What is the role of artistic approaches such as yours into the wider debate on the energy transition? What can be a contribution as an artist?

Judith: Firstly, artists offer a different perspective on certain topics. Artists provide a cultural context. In a way all man-made things, also technology, is culture. It helps to evaluate and reconsider one’s notions, opinions and ideas.

Secondly, it also allows a more emotional approach, something that can touch and reach into places that an argument on efficiency, investments and economics won’t ever achieve.

Art and culture are charging things or topics. It makes people more receptible and permeable because it offers additional value, enabling joy and well-being.

Thirdly, if you put art to work deliberately, it is a powerful translator and accelerator, that can help with the transition.

It sometimes seems as if those three things are the same, but they are not.

There is the possibility for artists to tap into new kinds of sources, reach new kinds of audiences. Artists can also be role models in leading a life based on more volatile values, taking more risks for one’s beliefs.

I’m teaching at the University for Applied Arts, discussing what impact or what role art and artists have in transitioning times, exploring environmental, technological and political topics that are important and vibrant.

Laure-Anne: From our perspective at PHOTORAMA, where we work with engineers and social scientists, this artistic approach could enrich projects like ours. When we talk about trying to make those topics relevant for society on a deeper level, understanding the emotional connection, as you said, to it and what it can make us fear, and what it says about us in society… Artistic approaches are very relevant to open a new set of people to those questions and for us to reflect on what we do.

Judith: With art, you can address issues that are difficult to communicate otherwise. It has a language of its own. People put a lot of trust in art because it tries to speak a truth that is not commercialised or coerced. It’s essential to support and preserve this culture and to support art and artists.

Laure-Anne: Thank you very much Judith for this very nice discussion! We hope to see more collaborations between art and technology in the future.

To see more of Judith’s work, visit her website here.

We also recommend checking her ‘sunset patterns’ project here.

[1] City of a thousand Planets (2017)